Beginnings of English Literature

This is taken from William J. Long’s Outlines of English and American Literature.

This is taken from William J. Long’s Outlines of English and American Literature.

Then the warrior, battle-tried, touched the sounding glee-wood:

Straight awoke the harp’s sweet note; straight a song uprose,

Sooth and sad its music. Then from hero’s lips there fell

A wonder-tale, well told.

Beowulf, line 2017 (a free rendering)

In its beginnings English literature is like a river, which proceeds not from a single wellhead but from many springs, each sending forth its rivulet of sweet or bitter water. As there is a place where the river assumes a character of its own, distinct from all its tributaries, so in English literature there is a time when it becomes national rather than tribal, and English rather than Saxon or Celtic or Norman. That time was in the fifteenth century, when the poems of Chaucer and the printing press of Caxton exalted the Midland above all other dialects and established it as the literary language of England.

Before that time, if you study the records of Britain, you meet several different tribes and races of men: the native Celt, the law-giving Roman, the colonizing Saxon, the sea-roving Dane, the feudal baron of Normandy, each with his own language and literature reflecting the traditions of his own people. Here in these old records is a strange medley of folk heroes, Arthur and Beowulf, Cnut and Brutus, Finn and Cuchulain, Roland and Robin Hood. Older than the tales of such folk-heroes are ancient riddles, charms, invocations to earth and sky:

Hal wes thu, Folde, fira moder!

Hail to thee, Earth, thou mother of men!

With these pagan spells are found the historical writings of the Venerable Bede, the devout hymns of Cædmon, Welsh legends, Irish and Scottish fairy stories, Scandinavian myths, Hebrew and Christian traditions, romances from distant Italy which had traveled far before the Italians welcomed them. All these and more, whether originating on British soil or brought in by missionaries or invaders, held each to its own course for a time, then met and mingled in the swelling stream which became English literature.

To trace all these tributaries to their obscure and lonely sources would require the labor of a lifetime. We shall here examine only the two main branches of our early literature, to the end that we may better appreciate the vigor and variety of modern English. The first is the Anglo-Saxon, which came into England in the middle of the fifth century with the colonizing Angles, Jutes and Saxons from the shores of the North Sea and the Baltic; the second is the Norman-French, which arrived six centuries later at the time of the Norman invasion. Except in their emphasis on personal courage, there is a marked contrast between these two branches, the former being stern and somber, the latter gay and fanciful. In Anglo-Saxon poetry we meet a strong man who cherishes his own ideals of honor, in Norman-French poetry a youth eagerly interested in romantic tales gathered from all the world. One represents life as a profound mystery, the other as a happy adventure.

* * * * *

ANGLO-SAXON OR OLD-ENGLISH PERIOD (450-1050)

SPECIMENS OF THE LANGUAGE.

Our English speech has changed so much in the course of centuries that it is now impossible to read our earliest records without special study; but that Anglo-Saxon is our own and not a foreign tongue may appear from the following examples. The first is a stanza from “Widsith,” the chant of a wandering gleeman or minstrel; and for comparison we place beside it Andrew Lang’s modern version. Nobody knows how old “Widsith” is; it may have been sung to the accompaniment of a harp that was broken fourteen hundred years ago. The second, much easier to read, is from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which was prepared by King Alfred from an older record in the ninth century:

Swa scrithende

gesceapum hweorfath,

Gleomen gumena

geond grunda fela;

Thearfe secgath,

thonc-word sprecath,

Simle, suth oththe north

sumne gemetath,

Gydda gleawne

geofam unhneawne.

So wandering on

the world about,

Gleemen do roam

through many lands;

They say their needs,

they speak their thanks,

Sure, south or north

someone to meet,

Of songs to judge

and gifts not grudge.

Her Hengest and Aesc, his sunu, gefuhton wid Bryttas on thaere stowe the is gecweden Creccanford, and thaer ofslogon feower thusenda wera. And tha Bryttas tha forleton Cent-lond, and mid myclum ege flugon to Lundenbyrig.

At this time Hengist and Esk, his son, fought with the Britons at the place that is called Crayford, and there slew four thousand men. And the Britons then forsook Kentland, and with much fear fled to London town.

BEOWULF.

The old epic poem, called after its hero Beowulf, is more than myth or legend, more even than history; it is a picture of a life and a world that once had real existence. Of that vanished life, that world of ancient Englishmen, only a few material fragments remain: a bit of linked armor, a rusted sword with runic inscriptions, the oaken ribs of a war galley buried with the Viking who had sailed it on stormy seas, and who was entombed in it because he loved it. All these are silent witnesses; they have no speech or language. But this old poem is a living voice, speaking with truth and sincerity of the daily habit of the fathers of modern England, of their adventures by sea or land, their stern courage and grave courtesy, their ideals of manly honor, their thoughts of life and death.

Let us hear, then, the story of Beowulf, picturing in our imagination the story-teller and his audience. The scene opens in a great hall, where a fire blazes on the hearth and flashes upon polished shields against the timbered walls. Down the long room stretches a table where men are feasting or passing a beaker from hand to hand, and anon crying Hal! hal! in answer to song or in greeting to a guest. At the head of the hall sits the chief with his chosen ealdormen. At a sign from the chief a gleeman rises and strikes a single clear note from his harp. Silence falls on the benches; the story begins:

Hail! we of the Spear Danes in days of old

Have heard the glory of warriors sung;

Have cheered the deeds that our chieftains wrought,

And the brave Scyld’s triumph o’er his foes.

Then because there are Scyldings present, and because brave men revere their ancestors, the gleeman tells a beautiful legend of how King Scyld came and went: how he arrived as a little child, in a war-galley that no man sailed, asleep amid jewels and weapons; and how, when his life ended at the call of Wyrd or Fate, they placed him against the mast of a ship, with treasures heaped around him and a golden banner above his head, gave ship and cargo to the winds, and sent their chief nobly back to the deep whence he came.

So with picturesque words the gleeman thrills his hearers with a vivid picture of a Viking’s sea-burial. It thrills us now, when the Vikings are no more, and when no other picture can be drawn by an eyewitness of that splendid pagan rite.

One of Scyld’s descendants was King Hrothgar (Roger) who built the hall Heorot, where the king and his men used to gather nightly to feast, and to listen to the songs of scop or gleeman. [Footnote:

Like Agamemnon and the Greek chieftains, every Saxon leader had his gleeman or minstrel, and had also his own poet, his scop or “shaper,” whose duty it was to shape a glorious deed into more glorious verse. So did our pagan ancestors build their monuments out of songs that should live in the hearts of men when granite or earth mound had crumbled away.] “There was joy of heroes,” but in one night the joy was changed to mourning. Out on the lonely fens dwelt the jotun (giant or monster) Grendel, who heard the sound of men’s mirth and quickly made an end of it. One night, as the thanes slept in the hall, he burst in the door and carried off thirty warriors to devour them in his lair under the sea. Another and another horrible raid followed, till Heorot was deserted and the fear of Grendel reigned among the Spear Danes. There were brave men among them, but of what use was courage when their weapons were powerless against the monster? “Their swords would not bite on his body.”

For twelve years this terror continued; then the rumor of Grendel reached the land of the Geats, where Beowulf lived at the court of his uncle, King Hygelac. No sooner did Beowulf hear of a dragon to be slain, of a friendly king “in need of a man,” than he selected fourteen companions and launched his war-galley in search of adventure.

At this point the old epic becomes a remarkable portrayal of daily life. In its picturesque lines we see the galley set sail, foam flying from her prow; we catch the first sight of the southern headlands, approach land, hear the challenge of the “warder of the cliffs” and Beowulf’s courteous answer. We follow the march to Heorot in war-gear, spears flashing, swords and byrnies clanking, and witness the exchange of greetings between Hrothgar and the young hero. Again is the feast spread in Heorot; once more is heard the song of gleemen, the joyous sound of warriors in comradeship. There is also a significant picture of Hrothgar’s wife, “mindful of courtesies,” honoring her guests by passing the mead-cup with her own hands. She is received by these stern men with profound respect.

When the feast draws to an end the fear of Grendel returns. Hrothgar warns his guests that no weapon can harm the monster, that it is death to sleep in the hall; then the Spear Danes retire, leaving Beowulf and his companions to keep watch and ward. With the careless confidence of brave men, forthwith they all fall asleep:

Forth from the fens, from the misty moorlands,

Grendel came gliding—God’s wrath he bore—

Came under clouds until he saw clearly, Glittering with gold plates, the mead-hall of men. Down fell the door, though hardened with fire-bands, Open it sprang at the stroke of his paw. Swollen with rage burst in the bale-bringer, Flamed in his eyes a fierce light, likest fire.

Throwing himself upon the nearest sleeper Grendel crushes and swallows him; then he stretches out a paw towards Beowulf, only to find it “seized in such a grip as the fiend had never felt before.” A desperate conflict begins, and a mighty uproar,–crashing of benches, shoutings of men, the “war-song” of Grendel, who is trying to break the grip of his foe. As the monster struggles toward the door, dragging the hero with him, a wide wound opens on his shoulder; the sinews snap, and with a mighty wrench Beowulf tears off the whole limb. While Grendel rushes howling across the fens, Beowulf hangs the grisly arm with its iron claws, “the whole grapple of Grendel,” over the door where all may see it.

Once more there is joy in Heorot, songs, speeches, the liberal giving of gifts. Thinking all danger past, the Danes sleep in the hall; but at midnight comes the mother of Grendel, raging to avenge her son. Seizing the king’s bravest companion she carries him away, and he is never seen again.

Here is another adventure for Beowulf. To old Hrothgar, lamenting his lost earl, the hero says simply:

Wise chief, sorrow not. For a man it is meet

His friend to avenge, not to mourn for his loss;

For death comes to all, but honor endures:

Let him win it who will, ere Wyrd to him calls,

And fame be the fee of a warrior dead!

Following the trail of the Brimwylf or Merewif (sea-wolf or sea-woman) Beowulf and his companions pass through desolate regions to a wild cliff on the shore. There a friend offers his good sword Hrunting for the combat, and Beowulf accepts the weapon, saying:

ic me mid Hruntinge Dom gewyrce, oththe mec death nimeth.

I with Hrunting Honor will win, or death shall me take.

Then he plunges into the black water, is attacked on all sides by the Grundwrygen or bottom monsters, and as he stops to fight them is seized by the Merewif and dragged into a cave, a mighty “sea-hall” free from water and filled with a strange light. On its floor are vast treasures; its walls are adorned with weapons; in a corner huddles the wounded Grendel. All this Beowulf sees in a glance as he turns to fight his new foe.

Follows then another terrific combat, in which the brand Hrunting proves useless. Though it rings out its “clanging war-song” on the monster’s scales, it will not “bite” on the charmed body. Beowulf is down, and at the point of death, when his eye lights on a huge sword forged by the jotuns of old. Struggling to his feet he seizes the weapon, whirls it around his head for a mighty blow, and the fight is won. Another blow cuts off the head of Grendel, but at the touch of the poisonous blood the steel blade melts like ice before the fire.

Leaving all the treasures, Beowulf takes only the golden hilt of the magic sword and the head of Grendel, reënters the sea and mounts up to his companions. They welcome him as one returned from the dead. They relieve him of helmet and byrnie, and swing away in a triumphal procession to Heorot. The hero towers among them, a conspicuous figure, and next to him comes the enormous head of Grendel carried on a spear-shaft by four of the stoutest thanes.

More feasting, gifts, noble speeches follow before the hero returns to his own land, laden with treasures. So ends the first part of the epic. In the second part Beowulf succeeds Hygelac as chief of the Geats, and rules them well for fifty years. Then a “firedrake,” guarding an immense hoard of treasure (as in most of the old dragon stories), begins to ravage the land. Once more the aged Beowulf goes forth to champion his people; but he feels that “Wyrd is close to hand,” and the fatalism which pervades all the poem is finely expressed in his speech to his companions. In his last fight he kills the dragon, winning the dragon’s treasure for his people; but as he battles amid flame and smoke the fire enters his lungs, and he dies “as dies a man,” paying for victory with his life. Among his last words is a command which reminds us again of the old Greeks, and of the word of Elpenor to Odysseus:

“Bid my brave men raise a barrow for me on the headland, broad, high, to be seen far out at sea: that hereafter sea-farers, driving their foamy keels through ocean’s mist, may behold and say, “Tis Beowulf’s mound!’”

The hero’s last words and the closing scenes of the epic, including the funeral pyre, the “bale-fire” and another Viking burial to the chant of armed men riding their war steeds, are among the noblest that have come down to us from beyond the dawn of history.

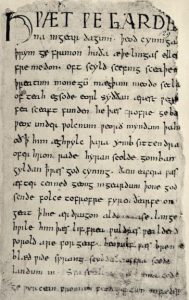

Such, in brief outline, is the story of Beowulf. It is recorded on a fire-marked manuscript, preserved as by a miracle from the torch of the Danes, which is now one of the priceless treasures of the British Museum. The handwriting indicates that the manuscript was copied about the year 1100, but the language points to the eighth or ninth century, when the poem in its present form was probably composed on English soil.

ANGLO-SAXON SONGS.

Beside the epic of Beowulf a few mutilated poems have been preserved, and these are as fragments of a plate or film upon which the life of long ago left its impression. One of the oldest of these poems is “Widsith,” the “wide-goer,” which describes the wanderings and rewards of the ancient gleeman. It begins:

Widsith spake, his word-hoard unlocked,

He who farthest had fared among earth-folk and tribe-folk.

Then follows a recital of the places he had visited, and the gifts he had received for his singing. Some of the personages named are real, others mythical; and as the list covers half a world and several centuries of time, it is certain that Widsith’s recital cannot be taken literally.

Two explanations offer themselves: the first, that the poem contains the work of many scops, each of whom added his travels to those of his predecessor; the second, that Widsith, like other gleemen, was both historian and poet, a keeper of tribal legends as well as a shaper of songs, and that he was ever ready to entertain his audience with things new or old. Thus, he mentioned Hrothgar as one whom he had visited; and if a hearer called for a tale at this point, the scop would recite that part of Beowulf which tells of the monster Grendel. Again, he named Sigard the Volsung (the Siegfrid of the Niebelungenlied and of Wagner’s opera), and this would recall the slaying of the dragon Fafnir, or some other story of the old Norse saga. So every name or place which Widsith mentioned was an invitation. When he came to a hall and “unlocked his word-hoard,” he offered his hearers a variety of poems and legends from which they made their own selection. Looked at in this way, the old poem becomes an epitome of Anglo-Saxon literature.

Other fragments of the period are valuable as indicating that the Anglo-Saxons were familiar with various types of poetry. “Deor’s Lament,” describing the sorrows of a scop who had lost his place beside his chief, is a true lyric; that is, a poem which reflects the author’s feeling rather than the deed of another man. In his grief the scop comforts himself by recalling the afflictions of various heroes, and he ends each stanza with the refrain:

That sorrow he endured; this also may I.

Among the best of the early poems are: “The Ruined City,” reflecting the feeling of one who looks on crumbling walls that were once the abode of human ambition; “The Seafarer,” a chantey of the deep, which ends with an allegory comparing life to a sea voyage; “The Wanderer,” which is the plaint of one who has lost home, patron, ambition, and as the easiest way out of his difficulty turns eardstappa, an “earth-hitter” or tramp;

“The Husband’s Message,” which is the oldest love song in our literature; and a few ballads and battle songs, such as “The Battle of Brunanburh” (familiar to us in Tennyson’s translation) and “The Fight at Finnsburgh,” which was mentioned by the gleemen in Beowulf, and which was then probably as well known as “The Charge of the Light Brigade” is to modern Englishmen.

Another early war song, “The Battle of Maldon” or “Byrhtnoth’s Death,” has seldom been rivaled in savage vigor or in the expression of deathless loyalty to a chosen leader. The climax of the poem is reached when the few survivors of an uneven battle make a ring of spears about their fallen chief, shake their weapons in the face of an overwhelming horde of Danes, while Byrhtwold, “the old comrade,” chants their defiance:

The sterner shall thought be, the bolder our hearts,

The greater the mood as lessens our might.

We know not when or by whom this stirring battle cry was written. It was copied under date of 991 in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, and is commonly called the swan song of Anglo-Saxon poetry. The lion song would be a better name for it.

LATER PROSE AND POETRY.

The works we have just considered were wholly pagan in spirit, but all reference to Thor or other gods was excluded by the monks who first wrote down the scop’s poetry.

With the coming of these monks a reform swept over pagan England, and literature reflected the change in a variety of ways. For example, early Anglo-Saxon poetry was mostly warlike, for the reason that the various earldoms were in constant strife; but now the peace of good will was preached, and moral courage, the triumph of self-control, was exalted above mere physical hardihood. In the new literature the adventures of Columb or Aidan or Brendan were quite as thrilling as any legends of Beowulf or Sigard, but the climax of the adventure was spiritual, and the emphasis was always on moral heroism.

Another result of the changed condition was that the unlettered scop, who carried his whole stock of poetry in his head, was replaced by the literary monk, who had behind him the immense culture of the Latin language, and who was interested in world history or Christian doctrine rather than in tribal fights or pagan mythology. These monks were capable men; they understood the appeal of pagan poetry, and their motto was, “Let nothing good be wasted.” So they made careful copy of the scop’s best songs (else had not a shred of early poetry survived), and so the pagan’s respect for womanhood, his courage, his loyalty to a chief,–all his virtues were recognized and turned to religious account in the new literature. Even the beautiful pagan scrolls, or “dragon knots,” once etched on a warrior’s sword, were reproduced in glowing colors in the initial letters of the monk’s illuminated Gospel.

A third result of the peaceful conquest of the missionaries was that many monasteries were established in Britain, each a center of learning and of writing. So arose the famous Northumbrian School of literature, to which we owe the writings of Bede, Cædmon, Cynewulf and others associated with certain old monasteries, such as Peterborough, Jarrow, York and Whitby, all north of the river Humber.

BEDE.

The good work of the monks is finely exemplified in the life of the Venerable Bede, or Bæda (cir. 673-735), who is well called the father of English learning. As a boy he entered the Benedictine monastery at Jarrow; the temper of his manhood may be judged from a single sentence of his own record:

“While attentive to the discipline of mine order and the daily care of singing in the church, my constant delight was in learning or teaching or writing.”

It is hardly too much to say that this gentle scholar was for half a century the teacher of Europe. He collected a large library of manuscripts; he was the author of some forty works, covering the whole field of human knowledge in his day; and to his school at Jarrow came hundreds of pupils from all parts of the British Isles, and hundreds more from the Continent. Of all his works the most notable is the so-called “Ecclesiastical History” (Historia ecclesiastica gentis anglorum) which should be named the “History of the Race of Angles.” This book marks the beginning of our literature of knowledge, and to it we are largely indebted for what we know of English history from the time of Cæsar’s invasion to the early part of the eighth century.

All the extant works of Bede are in Latin, but we are told by his pupil Cuthbert that he was “skilled in our English songs,” that he made poems and translated the Gospel of John into English. These works, which would now be of priceless value, were all destroyed by the plundering Danes.

As an example of Bede’s style, we translate a typical passage from his History. The scene is the Saxon Witenagemôt, or council of wise men, called by King Edward (625) to consider the doctrine of Paulinus, who had been sent from Rome by Pope Gregory. The first speaker is Coifi, a priest of the old religion:

“Consider well, O king, this new doctrine which is preached to us; for I now declare, what I have learned for certain, that the old religion has no virtue in it. For none of your people has been more diligent than I in the worship of our gods; yet many receive more favors from you, and are preferred above me, and are more prosperous in their affairs. If the old gods had any discernment, they would surely favor me, since I have been most diligent in their service. It is expedient, therefore, if this new faith that is preached is any more profitable than the old, that we accept it without delay.”

Whereupon Coifi, who as a priest has hitherto been obliged to ride upon an ass with wagging ears, calls loudly for a horse, a prancing horse, a stallion, and cavorts off, a crowd running at his heels, to hurl a spear into the shrine where he lately worshiped. He is a good type of the political demagogue, who clamors for progress when he wants an office, and whose spear is more likely to be hurled at the back of a friend than at the breast of an enemy.

Then a pagan chief rises to speak, and we bow to a nobler motive. His allegory of the mystery of life is like a strain of Anglo-Saxon poetry; it moves us deeply, as it moved his hearers ten centuries ago:

“This present life of man, O king, in comparison with the time that is hidden from us, is as the flight of a sparrow through the room where you sit at supper, with companions around you and a good fire on the hearth. Outside are the storms of wintry rain and snow. The sparrow flies in at one opening, and instantly out at another: whilst he is within he is sheltered from the winter storms, but after a moment of pleasant weather he speeds from winter back to winter again, and vanishes from your sight into the darkness whence he came. Even so the life of man appears for a little time; but of what went before and of what comes after we are wholly ignorant. If this new religion can teach us anything of greater certainty, it surely deserves to be followed.” [Footnote: Bede, Historia, Book II, chap xiii, a free translation]

CÆDMON (SEVENTH CENTURY).

In a beautiful chapter of Bede’s History we may read how Cædmon (d. 680) discovered his gift of poetry. He was, says the record, a poor unlettered servant of the Abbess Hilda, in her monastery at Whitby. At that time (and here is an interesting commentary on monastic culture) singing and poetry were so familiar that, whenever a feast was given, a harp would be brought in, and each monk or guest would in turn entertain the company with a song or poem to his own musical accompaniment. But Cædmon could not sing, and when he saw the harp coming down the table he would slip away ashamed, to perform his humble duties in the monastery:

“Now it happened once that he did this thing at a certain festivity, and went out to the stable to care for the horses, this duty being assigned him for that night. As he slept at the usual time one stood by him, saying, ‘Cædmon, sing me something.’ He answered, ‘I cannot sing, and that is why I came hither from the feast.’ But he who spake unto him said again, ‘Cædmon, sing to me.’ And he said, ‘What shall I sing?’ And that one said, ‘Sing the beginning of created things.’ Thereupon Cædmon began to sing verses that he had never heard before, of this import:

Nu scylun hergan hefaenriches ward …

Now shall we hallow the warden of heaven,

He the Creator, he the Allfather,

Deeds of his might and thoughts of his mind….”

In the morning he remembered the words, and came humbly to the monks to recite the first recorded Christian hymn in our language. And a very noble hymn it is. The monks heard him in wonder, and took him to the Abbess Hilda, who gave order that Cædmon should receive instruction and enter the monastery as one of the brethren. Then the monks expounded to him the Scriptures. He in turn, reflecting on what he had heard, echoed it back to the monks “in such melodious words that his teachers became his pupils.” So, says the record, the whole course of Bible history was turned into excellent poetry.

About a thousand years later, in the days of Milton, an Anglo-Saxon manuscript was discovered containing a metrical paraphrase of the books of Genesis, Exodus and Daniel, and these were supposed to be some of the poems mentioned in Bede’s narrative. A study of the poems (now known as the Cædmonian Cycle) leads to the conclusion that they were probably the work of two or three writers, and it has not been determined what part Cædmon had in their composition. The nobility of style in the Genesis poem and the picturesque account of the fallen angels (which reappears in Paradise Lost) have won for Cædmon his designation as the Milton of the Anglo-Saxon period. [Footnote: A friend of Milton, calling himself Franciscus Junius, first printed the Cædmon poems in Antwerp (cir. 1655) during Milton’s lifetime. The Puritan poet was blind at the time, and it is not certain that he ever saw or heard the poems; yet there are many parallelisms in the earlier and later works which warrant the conclusion that Milton was influenced by Cædmon’s work.]

CYNEWULF (EIGHTH CENTURY).

There is a variety of poems belonging to the Cynewulf Cycle, and of some of these Cynewulf (born cir. 750) was certainly the author, since he wove his name into the verses in the manner of an acrostic. Of Cynewulf’s life we know nothing with certainty; but from various poems which are attributed to him, and which undoubtedly reflect some personal experience, scholars have constructed the following biography,–which may or may not be true.

In his early life Cynewulf was probably a wandering scop of the old pagan kind, delighting in wild nature, in adventure, in the clamor of fighting men. To this period belong his “Riddles” [Footnote: These riddles are ancient conundrums, in which some familiar object, such as a bow, a ship, a storm lashing the shore, the moon riding the clouds like a Viking’s boat, is described in poetic language, and the last line usually calls on the hearer to name the object described. See Cook and Tinker, Translations from Old English Poetry.] and his vigorous descriptions of the sea and of battle, which show hardly a trace of Christian influence. Then came trouble to Cynewulf, perhaps in the ravages of the Danes, and some deep spiritual experience of which he writes in a way to remind us of the Puritan age:

“In the prison of the night I pondered with myself. I was stained with my own deeds, bound fast in my sins, hard smitten with sorrows, walled in by miseries.”

A wondrous vision of the cross, “brightest of beacons,” shone suddenly through his darkness, and led him forth into light and joy. Then he wrote his “Vision of the Rood” and probably also Juliana and The Christ. In the last period of his life, a time of great serenity, he wrote Andreas, a story of St. Andrew combining religious instruction with extraordinary adventure; Elene, which describes the search for the cross on which Christ died, and which is a prototype of the search for the Holy Grail; and other poems of the same general kind. [Footnote: There is little agreement among scholars as to who wrote most of these poems. The only works to which Cynewulf signs his name are The Christ, Elene, Juliana and Fates of the Apostles. All others are doubtful, and our biography of Cynewulf is largely a matter of pleasant speculation.] Aside from the value of these works as a reflection of Anglo-Saxon ideals, they are our best picture of Christianity as it appeared in England during the eighth and ninth centuries.

ALFRED THE GREAT

(848-901). We shall understand the importance of Alfred’s work if we remember how his country fared when he became king of the West Saxons, in 871. At that time England lay at the mercy of the Danish sea-rovers. Soon after Bede’s death they fell upon Northumbria, hewed out with their swords a place of settlement, and were soon lords of the whole north country. Being pagans (“Thor’s men” they called themselves) they sacked the monasteries, burned the libraries, made a lurid end of the civilization which men like Columb and Bede had built up in North-Humberland. Then they pushed southward, and were in process of paganizing all England when they were turned back by the heroism of Alfred. How he accomplished his task, and how from his capital at Winchester he established law and order in England, is recorded in the histories. We are dealing here with literature, and in this field Alfred is distinguished in two ways: first, by his preservation of early English poetry; and second, by his own writing, which earned for him the title of father of English prose. Finding that some fragments of poetry had escaped the fire of the Danes, he caused search to be made for old manuscripts, and had copies made of all that were legible. [Footnote: These copies were made in Alfred’s dialect (West Saxon) not in the Northumbrian dialect in which they were first written.] But what gave Alfred deepest concern was that in all his kingdom there were few priests and no laymen who could read or write their own language. As he wrote sadly:

“King Alfred sends greeting to Bishop Werfrith in words of love and friendship. Let it be known to thee that it often comes to my mind what wise men and what happy times were formerly in England, … I remember what I saw before England had been ravaged and burned, how churches throughout the whole land were filled with treasures of books. And there was also a multitude of God’s servants, but these had no knowledge of the books: they could not understand them because they were not written in their own language. It was as if the books said, ‘Our fathers who once occupied these places loved wisdom, and through it they obtained wealth and left it to us. We see here their footprints, but we cannot follow them, and therefore have we lost both their wealth and their wisdom, because we would not incline our hearts to their example.’ When I remember this, I marvel that good and wise men who were formerly in England, and who had learned these books, did not translate them into their own language. Then I answered myself and said, ‘They never thought that their children would be so careless, or that learning would so decay.’” [Footnote: A free version of part of Alfred’s preface to his translation of Pope Gregory’s Cura Pastoralis, which appeared in English as the Hirdeboc or Shepherd’s Book.]

To remedy the evil, Alfred ordered that every freeborn Englishman should learn to read and write his own language; but before he announced the order he followed it himself. Rather late in his boyhood he had learned to spell out an English book; now with immense difficulty he took up Latin, and translated the best works for the benefit of his people. His last notable work was the famous Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

At that time it was customary in monasteries to keep a record of events which seemed to the monks of special importance, such as the coming of a bishop, the death of a king, an eclipse of the moon, a battle with the Danes. Alfred found such a record at Winchester, rewrote it (or else caused it to be rewritten) with numerous additions from Bede’s History and other sources, and so made a fairly complete chronicle of England. This was sent to other monasteries, where it was copied and enlarged, so that several different versions have come down to us. The work thus begun was continued after Alfred’s death, until 1154, and is the oldest contemporary history possessed by any modern nation in its own language.

* * * * *

ANGLO-NORMAN OR MIDDLE-ENGLISH PERIOD (1066-1350)

SPECIMENS OF THE LANGUAGE. A glance at the following selections will show how Anglo-Saxon was slowly approaching our English speech of to-day. The first is from a religious book called Ancren Riwle (Rule of the Anchoresses, cir. 1225). The second, written about a century later, is from the riming chronicle, or verse history, of Robert Manning or Robert of Brunne. In it we note the appearance of rime, a new thing in English poetry, borrowed from the French, and also a few words, such as “solace,” which are of foreign origin:

“Hwoso hevide iseid to Eve, theo heo werp hire eien therone, ‘A! wend te awei; thu worpest eien o thi death!’ hwat heved heo ionswered? ‘Me leove sire, ther havest wouh. Hwarof kalenges tu me? The eppel that ich loke on is forbode me to etene, and nout forto biholden.’”

“Whoso had said (or, if anyone had said) to Eve when she cast her eye theron (i.e. on the apple) ‘Ah! turn thou away; thou castest eyes on thy death!’ what would she have answered? ‘My dear sir, thou art wrong. Of what blamest thou me? The apple which I look upon is forbidden me to eat, not to behold.’”

Lordynges that be now here,

If ye wille listene and lere

All the story of Inglande,

Als Robert Mannyng wryten it fand,

And on Inglysch has it schewed,

Not for the lered but for the lewed,

For tho that on this land wonn

That ne Latin ne Frankys conn,

For to hauf solace and gamen

In felauschip when they sitt samen;

And it is wisdom for to wytten

The state of the land, and haf it wryten.

THE NORMAN CONQUEST.

For a century after the Norman conquest native poetry disappeared from England, as a river may sink into the earth to reappear elsewhere with added volume and new characteristics. During all this time French was the language not only of literature but of society and business; and if anyone had declared at the beginning of the twelfth century, when Norman institutions were firmly established in England, that the time was approaching when the conquerors would forget their fatherland and their mother tongue, he would surely have been called dreamer or madman. Yet the unexpected was precisely what happened, and the Norman conquest is remarkable alike for what it did and for what it failed to do.

It accomplished, first, the nationalization of England, uniting the petty Saxon earldoms into one powerful kingdom; and second, it brought into English life, grown sad and stern, like a man without hope, the spirit of youth, of enthusiasm, of eager adventure after the unknown,–in a word, the spirit of romance, which is but another name for that quest of some Holy Grail in which youth is forever engaged.

NORMAN LITERATURE.

One who reads the literature that the conquerors brought to England must be struck by the contrast between the Anglo-Saxon and the Norman-French spirit. For example, here is the death of a national hero as portrayed in The Song of Roland, an old French epic, which the Normans first put into polished verse:

Li quens Rollans se jut desuz un pin,

Envers Espaigne en ad turnet son vis,

De plusurs choscs a remembrer le prist….

“Then Roland placed himself beneath a pine tree. Towards Spain he turned his face. Of many things took he remembrance: of various lands where he had made conquests; of sweet France and his kindred; of Charlemagne, his feudal lord, who had nurtured him. He could not refrain from sighs and tears; neither could he forget himself in need. He confessed his sins and besought the Lord’s mercy. He raised his right glove and offered it to God; Saint Gabriel from his hand received the offering. Then upon his breast he bowed his head; he joined his hands and went to his end. God sent down his cherubim, and Saint Michael who delivers from peril. Together with Saint Gabriel they departed, bearing the Count’s soul to Paradise.”

We have not put Roland’s ceremonious exit into rime and meter; neither do we offer any criticism of a scene in which the death of a national hero stirs no interest or emotion, not even with the help of Gabriel and the cherubim. One is reminded by contrast of Scyld, who fares forth alone in his Viking ship to meet the mystery of death; or of that last scene of human grief and grandeur in Beowulf where a few thanes bury their dead chief on a headland by the gray sea, riding their war steeds around the memorial mound with a chant of sorrow and victory.

The contrast is even more marked in the mass of Norman literature: in romances of the maidens that sink underground in autumn, to reappear as flowers in spring; of Alexander’s journey to the bottom of the sea in a crystal barrel, to view the mermaids and monsters; of Guy of Warwick, who slew the giant Colbrant and overthrew all the knights of Europe, just to win a smile from his Felice; of that other hero who had offended his lady by forgetting one of the commandments of love, and who vowed to fill a barrel with his tears, and did it. The Saxons were as serious in speech as in action, and their poetry is a true reflection of their daily life; but the Normans, brave and resourceful as they were in war and statesmanship, turned to literature for amusement, and indulged their lively fancy in fables, satires, garrulous romances, like children reveling in the lore of elves and fairies. As the prattle of a child was the power that awakened Silas Marner from his stupor of despair, so this Norman element of gayety, of exuberant romanticism, was precisely what was needed to rouse the sterner Saxon mind from its gloom and lethargy.

THE NEW NATION.

So much, then, the Normans accomplished: they brought nationality into English life, and romance into English literature. Without essentially changing the Saxon spirit they enlarged its thought, aroused its hope, gave it wider horizons. They bound England with their laws, covered it with their feudal institutions, filled it with their ideas and their language; then, as an anticlimax, they disappeared from English history, and their institutions were modified to suit the Saxon temperament. The race conquered in war became in peace the conquerors. The Normans speedily forgot France, and even warred against it. They began to speak English, dropping its cumbersome Teutonic inflections, and adding to it the wealth of their own fine language. They ended by adopting England as their country, and glorifying it above all others. “There is no land in the world,” writes a poet of the thirteenth century, “where so many good kings and saints have lived as in the isle of the English. Some were holy martyrs who died cheerfully for God; others had strength or courage like to that of Arthur, Edmund and Cnut.”

This poet, who was a Norman monk at Westminster Abbey, wrote about the glories of England in the French language, and celebrated as the national heroes a Celt, a Saxon and a Dane.

So in the space of two centuries a new nation had arisen, combining the best elements of the Anglo-Saxon and Norman-French people, with a considerable mixture of Celtic and Danish elements. Out of the union of these races and tongues came modern English life and letters.

GEOFFREY AND THE LEGENDS OF ARTHUR.

Geoffrey of Monmouth was a Welshman, familiar from his youth with Celtic legends; also he was a monk who knew how to write Latin; and the combination was a fortunate one, as we shall see.

Long before Geoffrey produced his celebrated History (cir. 1150), many stories of the Welsh hero Arthur [Footnote: Who Arthur was has never been determined. There was probably a chieftain of that name who was active in opposing the Anglo-Saxon invaders of Britain, about the year 500; but Gildas, who wrote a Chronicle of Britain only half a century later, does not mention him; neither does Bede, who made study of all available records before writing his History. William of Malmesbury, a chronicler of the twelfth century, refers to “the warlike Arthur of whom the Britons tell so many extravagant fables, a man to be celebrated not in idle tales but in true history.” He adds that there were two Arthurs, one a Welsh war-chief (not a king), and the other a myth or fairy creation. This, then, may be the truth of the matter, that a real Arthur, who made a deep impression on the Celtic imagination, was soon hidden in a mass of spurious legends. That Bede had heard these legends is almost certain; that he did not mention them is probably due to the fact that he considered Arthur to be wholly mythical.] were current in Britain and on the Continent; but they were never written because of a custom of the Middle Ages which required that, before a legend could be recorded, it must have the authority of some Latin manuscript. Geoffrey undertook to supply such authority in his Historia regum britanniae, or History of the Kings of Britain, in which he proved Arthur’s descent from Roman ancestors. [Note: After the landing of the Romans in Britain a curious mingling of traditions took place, and in Geoffrey’s time native Britons considered themselves as children of Brutus of Rome, and therefore as grandchildren of Æneas of Troy.] He quoted liberally from an ancient manuscript which, he alleged, established Arthur’s lineage, but which he did not show to others. A storm instantly arose among the writers of that day, most of whom denounced Geoffrey’s Latin manuscript as a myth, and his History as a shameless invention. But he had shrewdly anticipated such criticism, and issued this warning to the historians, which is solemn or humorous according to your point of view:

“I forbid William of Malmesbury and Henry of Huntingdon to speak of the kings of Britain, since they have not seen the book which Walter Archdeacon of Oxford [who was dead, of course] brought out of Brittany.”

It is commonly believed that Geoffrey was an impostor, but in such matters one should be wary of passing judgment. Many records of men, cities, empires, have suddenly arisen from the tombs to put to shame the scientists who had denied their existence; and it is possible that Geoffrey had seen one of the legion of lost manuscripts. The one thing certain is, that if he had any authority for his History he embellished the same freely from popular legends or from his own imagination, as was customary at that time.

His work made a sensation. A score of French poets seized upon his Arthurian legends and wove them into romances, each adding freely to Geoffrey’s narrative. The poet Wace added the tale of the Round Table, and another poet (Walter Map, perhaps) began a cycle of stories concerning Galahad and the quest of the Holy Grail. [Note: The Holy Grail, or San Graal, or Sancgreal, was represented as the cup from which Christ drank with his disciples at the Last Supper. Legend said that the sacred cup had been brought to England, and Arthur’s knights undertook, as the most compelling of all duties, to search until they found it.]

The origin of these Arthurian romances, which reappear so often in English poetry, is forever shrouded in mystery. The point to remember is, that we owe them all to the genius of the native Celts; that it was Geoffrey of Monmouth who first wrote them in Latin prose, and so preserved a treasure which else had been lost; and that it was the French trouvères, or poets, who completed the various cycles of romances which were later collected in Malory’s Morte d’ Arthur.

TYPES OF MIDDLE-ENGLISH LITERATURE.

It has long been customary to begin the study of English literature with Chaucer; but that does not mean that he invented any new form of poetry or prose. To examine any collection of our early literature, such as Cook’s Middle-English Reader, is to discover that many literary types were flourishing in Chaucer’s day, and that some of these had grown old-fashioned before he began to use them.

In the thirteenth century, for example, the favorite type of literature in England was the metrical romance, which was introduced by the French poets, and written at first in the French language. The typical romance was a rambling story dealing with the three subjects of love, chivalry and religion; it was filled with adventures among giants, dragons, enchanted castles; and in that day romance was not romance unless liberally supplied with magic and miracle. There were hundreds of such wonder-stories, arranged loosely in three main groups: the so-called “matter of Rome” dealt with the fall of Troy in one part, and with the marvelous adventures of Alexander in the other; the “matter of France” celebrated the heroism of Charlemagne and his Paladins; and the “matter of Britain” wove the magic web of romance around Arthur and his knights of the Round Table.

One of the best of the metrical romances is “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight,” which may be read as a measure of all the rest. If, as is commonly believed, the unknown author of “Sir Gawain” wrote also “The Pearl” (a beautiful old elegy, or poem of grief, which immortalizes a father’s love for his little girl), he was the greatest poet of the early Middle-English period. Unfortunately for us, he wrote not in the king’s English or speech of London (which became modern English) but in a different dialect, and his poems should be read in a present-day version; else will the beauty of his work be lost in our effort to understand his language.

Other types of early literature are the riming chronicles or verse histories (such as Layamon’s Brut, a famous poem, in which the Arthurian legends appear as part of English history), stories of travel, translations, religious poems, books of devotion, miracle plays, fables, satires, ballads, hymns, lullabies, lyrics of love and nature,–an astonishing collection for so ancient a time, indicative at once of our changing standards of poetry and of our unchanging human nature. For the feelings which inspired or gave welcome to these poems, some five or six hundred years ago, are precisely the same feelings which warm the heart of a poet and his readers to-day. There is nothing ancient but the spelling in this exquisite Lullaby, for instance, which was sung on Christmas eve:

He cam also stylle

Ther his moder was

As dew in Aprylle

That fallyt on the gras;

He cam also stylle

To his moderes bowr

As dew in Aprylle

That fallyt on the flour;

He cam also stylle

Ther his moder lay

As dew in Aprylle

That fallyt on the spray.

Or witness this other fragment from an old love song, which reflects the feeling of one who “would fain make some mirth” but who finds his heart sad within him:

Now wold I fayne som myrthis make

All oneli for my ladys sake,

When I hir se;

But now I am so ferre from hir

Hit will nat be.

Thogh I be long out of hir sight,

I am hir man both day and night,

And so will be;

Wherfor, wold God as I love hir

That she lovd me!When she is mery, then I am glad;

When she is sory, then am I sad,

And causë whi:

For he livith nat that lovith hir

So well as I.She sayth that she hath seen hit wreten

That ‘seldyn seen is soon foryeten.’

Hit is nat so;

For in good feith, save oneli hir,

I love no moo.Wherfor I pray, both night and day,

That she may cast al care away,

And leve in rest

That evermo, where’er she be,

I love hir best;

And I to hir for to be trew,

And never chaunge her for noon new

Unto myne ende;

And that I may in hir servise

For evyr amend.

* * * * *

SUMMARY OF BEGINNINGS.

The two main branches of our literature are the Anglo-Saxon and the Norman-French, both of which received some additions from Celtic, Danish and Roman sources. The Anglo-Saxon literature came to England with the invasion of Teutonic tribes, the Angles, Saxons and Jutes (cir. 449). The Norman-French literature appeared after the Norman conquest of England, which began with the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

The Anglo-Saxon literature is classified under two heads, pagan and Christian. The extant fragments of pagan literature include one epic or heroic poem, Beowulf, and several lyrics and battle songs, such as “Widsith,” “Deor’s Lament,” “The Seafarer,” “The Battle of Brunanburh” and “The Battle of Maldon.” All these were written at an unknown date, and by unknown poets.

The best Christian literature of the period was written in the Northumbrian and the West-Saxon schools. The greatest names of the Northumbrian school are Bede, Cædmon and Cynewulf. The most famous of the Wessex writers is Alfred the Great, who is called “the father of English prose.”

The Normans were originally Northmen, or sea rovers from Scandinavia, who settled in northern France and adopted the Franco-Latin language and civilization. With their conquest of England, in the eleventh century, they brought nationality into English life, and the spirit of romance into English literature. Their stories in prose or verse were extremely fanciful, in marked contrast with the stern, somber poetry of the Anglo-Saxons.

The most notable works of the Norman-French period are: Geoffrey’s History of the Kings of Britain, which preserved in Latin prose the native legends of King Arthur; Layamon’s Brut, a riming chronicle or verse history in the native tongue; many metrical romances, or stories of love, chivalry, magic and religion; and various popular songs and ballads. The greatest poet of the period is the unknown author of “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” (a metrical romance) and probably also of “The Pearl,” a beautiful elegy, which is our earliest In Memoriam.

SELECTIONS FOR READING.

Without special study of Old English it is impossible to read our earliest literature. The beginner may, however, enter into the spirit of that literature by means of various modern versions, such as the following:

Beowulf. Garnett’s Beowulf (Ginn and Company), a literal translation, is useful to those who study Anglo-Saxon, but is not very readable. The same may be said of Gummere’s The Oldest English Epic, which follows the verse form of the original. Two of the best versions for the beginner are Child’s Beowulf, in Riverside Literature Series (Houghton), and Earle’s The Deeds of Beowulf (Clarendon Press).

Anglo-Saxon Poetry. The Seafarer, The Wanderer, The Husband’s Message (or Love Letter), Deor’s Lament, Riddles, Battle of Brunanburh, selections from The Christ, Andreas, Elene, Vision of the Rood, and The Phoenix,–all these are found in an excellent little volume, Cook and Tinker, Translations from Old English Poetry (Ginn and Company).

Anglo-Saxon Prose. Good selections in Cook and Tinker, Translations from Old English Prose (Ginn and Company). Bede’s History, translated in Everyman’s Library (Dutton) and in the Bohn Library (Macmillan). In the same volume of the Bohn Library is a translation of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Alfred’s Orosius (with stories of early exploration) translated in Pauli’s Life of Alfred.

Norman-French Period. Selections in Manly, English Poetry, and English Prose (Ginn and Company); also in Morris and Skeat, Specimens of Early English (Clarendon Press). The Song of Roland in Riverside Literature Series, and in King’s Classics. Selected metrical romances in Ellis, Specimens of Early English Metrical Romances (Bohn Library); also in Morley, Early English Prose Romances, and in Carisbrooke Library Series. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, modernized by Weston, in Arthurian Romances Series. Andrew Lang, Aucassin and Nicolette (Crowell). The Pearl, translated by Jewett (Crowell), and by Weir Mitchell (Century). Selections from Layamon’s Brut in Morley, English Writers, Vol. III. Geoffrey’s History in Everyman’s Library, and in King’s Classics. The Arthurian legends in The Mabinogion (Everyman’s Library); also in Sidney Lanier’s The Boy’s King Arthur and The Boy’s Mabinogion (Scribner). A good single volume containing the best of Middle-English literature, with notes, is Cook, A Literary Middle-English Reader (Ginn and Company).

BIBLIOGRAPHY. For extended works covering the entire field of English history and literature, and for a list of the best anthologies, school texts, etc., see the General Bibliography. The following works are of special interest in studying early English literature.

HISTORY. Allen, Anglo-Saxon Britain; Turner, History of the Anglo-Saxons; Ramsay, The Foundations of England; Freeman, Old English History; Cook, Life of Alfred; Freeman, Short History of the Norman Conquest; Jewett, Story of the Normans, in Stories of the Nations.

LITERATURE. Brooke, History of Early English Literature; Jusserand, Literary History of the English People, Vol. I; Ten Brink, English Literature, Vol. I; Lewis, Beginnings of English Literature; Schofield, English Literature from the Norman Conquest to Chaucer; Brother Azarias, Development of Old-English Thought; Mitchell, From Celt to Tudor; Newell, King Arthur and the Round Table. A more advanced work on Arthur is Rhys, Studies in the Arthurian Legends.

FICTION AND POETRY. Kingsley, Hereward the Wake; Lytton, Harold Last of the Saxon Kings; Scott, Ivanhoe; Kipling, Puck of Pook’s Hill; Jane Porter, Scottish Chiefs; Shakespeare, King John; Tennyson, Becket, and The Idylls of the King; Gray, The Bard; Bates and Coman, English History Told by English Poets.