(This is taken from W. Roberts' The Book-Hunter in London.)

As a second-hand bookselling locality, Holborn is one of the oldest of those in which the trade is still carried on vigorously. As a bookselling locality it has a record of close on three centuries and a half. As early as 1558, a publisher was issuing cheap books in connection with John Tisdale, at the Saracen's Head, in Holborn, near to the Conduit, and in one of these booklets we are enjoined to

'Remember, man! both night and day,

Thou needs must die, there is no Nay.'

Probably the earliest, and certainly one of the earliest, books published in Holborn was the 'Vision of Piers Plowman,' 'now fyrst imprinted by Robert Crowley, dwellyng in Ely-rents in Holburne,' in 1550, which contains a very quaint address from the printer. In and about the year 1584, Roger Warde, a very prolific publisher, was dwelling near 'Holburne Conduit, at the sign of the "Talbot,"' and a still more noteworthy individual, Richard Jones, lived hard by, at the sign of the Rose and Crown.

Early in the seventeenth century, several members of the fraternity had established themselves in and around Gray's Inn Gate, then termed, more appropriately, Lane. Henrie Tomes published 'The Commendation of Cocks and Cock-fighting' (1607), which, no doubt, the 'young bloods' of the period perused much more diligently than more instructive and edifying books with which Mr. Tomes also could have supplied them.

Its most famous bibliopolic resident, however, is Thomas Osborne, or Tom Osborne, as he was called in the trade and by posterity. Tom Osborne's fame began and ended with himself. Nobody knew whence he came, and probably nobody cared. His catalogues cover a period of thirty years—1738-1768—and include some very remarkable libraries of many famous men. In stature he is described as short and thick, so that Dr. Johnson's famous summary method of knocking him down was not perhaps so difficult a feat as is generally supposed. To his inferiors—including, as he apparently but ruefully thought, Dr. Johnson—he generally spoke in an authoritative and insolent manner. As ignorant as Lackington, he was considerably less aware of the fact. Osborne's shop, like that of Jacob Tonson at the end of the seventeenth and beginning of the eighteenth centuries, was at the Gray's Inn Road gate of, or entrance to, Gray's Inn. His greatest coup was the purchase of the Harleian Collection of books—the manuscripts were bought by the British Museum for £10,000—for £13,000, in 1743. It is said on good authority that the Earl of Oxford gave £18,000 for the binding of only a part of them. In 1743-44, the extent of this extraordinary collection was indicated by the 'Catalogus Bibliotheca Harleianæ,' in four volumes. The first two, in Latin, were compiled by Dr. Johnson at a daily wage, and the third and fourth (which are a repetition of the first two), in English, are by Oldys. A charge of 5s. was made for the first two volumes, which caused a good deal of grumbling among the trade, and was resented 'as an avaricious innovation,' but Osborne replied that the volumes could be either returned in exchange for books or for the original purchase-money. He was also charged with rating his books at too high a price, but a glance through the catalogue will prove this to be an unjust accusation. The copy of the Aldine Plato, 1513, on vellum, for which Lord Oxford gave 100 guineas, is priced by Osborne at £21. The sale of the books appears to have been extremely slow, and Johnson assured Boswell that 'there was not much gained by the bargain.' Nichols' 'Literary Anecdotes' (iii. 649-654) gives a list of the libraries which Osborne absorbed into his stock at different times, but few of these are anything more than names at the present day. Osborne is satirized in the 'Dunciad,' but, according to Johnson, was so dull that he could not feel the poet's gross satire. Sir John Hawkins states that Osborne used to boast that he was worth £40,000, and doubtless this was true. His

'Bushy bob, well powder'd every day,

Bloom'd whiter than a hawthorn hedge in May,'

was one of his acquired peculiarities. Nichols tells us that the expression 'rum books' arose from Osborne's sending unsaleable volumes to Jamaica in exchange for rum.

But whilst Tom Osborne was the bookseller of Holborn, there were many others well established here during the last century, and whose names have been handed down to us by the catalogues which they published. William Cater, for instance, was issuing catalogues from Holborn in 1767, when he sold the libraries of Lord Willoughby, president of the Society of Antiquaries, and in 1774 of Cudworth Bruck, another antiquary. Cater was succeeded in 1786 by John Deighton, of Cambridge. In the person of Henry Dell we get a literary bookseller, who had established himself first in Tower Street, and in or about 1765 in Holborn, where, Nichols tells us, he died very poor. He wrote 'The Booksellers, a Poem,' 1766, which has been pronounced 'a wretched, rhyming list of booksellers in London, and Westminster, with silly commendations of some and stupid abuse of others.' Other Holborn booksellers were: William Fox, 1773-1777; John Hayes, who died November 12, 1811, aged seventy-four, and 'whose abilities were of no ordinary class, and his erudition very considerable'; John Anderson, of Holborn Hill, 1787-1792, who sold the library of the Hon. John Scott, of Gray's Inn; Francis Noble, who, besides being a bookseller, kept for many years an extensive circulating library in Holborn, but who, in consequence of his daughter's obtaining a share in the first £30,000 prize in the lottery, retired from business, and died at an advanced age in June, 1792; Joseph White, 1779-1791; and William Flexney, who died January 7, 1808, aged seventy-seven, and who was the original publisher of Churchill's 'Poems,' and is thus immortalized by that versatile 'poet':

"Let those who energy of diction prize,

For Billingsgate, quit Flexney, and be wise."

Percival Stockdale, in his 'Memoirs,' speaks highly of his 'old friend' Flexney, 'with whom I have passed many convivial and jovial hours.'

J. H. Prince, of Old North Street, Red Lion Square, Holborn, who wrote and published his own eccentric 'Life' in 1806, and who, trying and failing in nearly everything else, took to bookselling and book-writing, evidently, like many other authors before and since, found soliciting subscriptions for his book 'a most painful undertaking to a susceptible mind.' His motto was, 'I evil ni etips,' or 'I live in spite.' A much more important bookseller of Holborn was John Petheram, who lived at 94, High Holborn in the fifties, and whose catalogues were styled 'The Bibliographical Miscellany'; for some time, with each of his catalogues he issued an eight-page supplement, which consisted of a reprint of some very rare tract; the selection of some of these was in the hands of Dr. E. F. Rimbault. A complete set of these catalogues would be extremely interesting; we have only seen half a dozen of them, and these are in the British Museum. A somewhat similar effort to give an extra interest to catalogues was made a few years ago by J. W. Jarvis and Son, of King William Street, and also by Pickering and Chatto, the Haymarket; but the experiment apparently did not succeed.

Apart from Holborn, properly so called, Middle Row, an insulated row of houses, abutting upon Holborn Bars, and nearly opposite Gray's Inn Road, claims a notice here, for it was long a book-hunting locality, and two bookshops, at least, existed there until the place was demolished in August, 1867. Perhaps its most famous bookseller was John Cuthell, who came to London from Scotland in 1771, and became assistant to Drew, of Middle Row, whom he succeeded. He was publishing catalogues here from 1787, and did a very large export business with America. He was noted for his stock of medical and scientific books. He was still at Middle Row in 1813, when John Nichols published his 'Literary Anecdotes,' to which he was a subscriber. Cuthell died at Turnham Green in 1828, aged eighty-five. He was succeeded by Francis Macpherson, who issued the thirtieth number of his catalogue in April, 1840, from No. 4, Middle Row. The works offered comprised a selection of theological, classical, and historical books. One of the most curious entries relates to an extensive collection of books and pamphlets by and concerning the famous Dr. Richard Bentley, five volumes in quarto, and thirty-one more in octavo and duodecimo; the set (now, we believe, in the British Museum), doubtless the most complete ever offered for sale, was priced at £25, and was probably utilized in Dyce's editions of Bentley's 'Dissertations,' and in an edition of Bentley's 'Sermons at Boyle's Lecture,' both of which Macpherson published. This catalogue is interesting from the number of illustrations which it affords of the transition period of English book-collecting; the various editions of the classics are priced at very moderate figures, whilst English classics are offered at comparatively 'fancy' sums. For example, a very neat copy of the first edition of 'Tom Jones' is offered at 18s., and a fine copy of John Bale's 'Image of Both Churches,' without date, but printed by East at the latter part of the sixteenth century, at £1 7s. J. Coxhead is another Holborn bookseller who may be regarded as a link between the old and the new. He was at 249, High Holborn in 1840, and had been established forty years. His lists were apparently issued only once or twice a year; one of the notices in his catalogue may be quoted here, as showing the chief medium by which country book-collectors were supplied with their books: 'Gentlemen residing in the country had better apply direct to J. Coxhead for any articles from this list, or they can obtain them by giving the order to their country bookseller, and it will be sent in their weekly parcel from London.' At about the same time, and for nearly the same period, David Ogilby was selling second-hand books at the same locality.

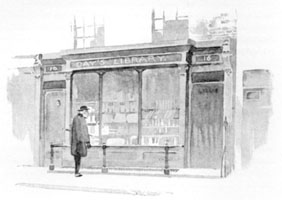

One of the most interesting of the Holborn booksellers was William Darton, of 58, Holborn Hill, of whose shop we give an 'interior' view from a plate engraved by Darton himself. William was a son of William Darton, who founded the famous publishing house of Darton and Harvey, of 55, Gracechurch Street, in the latter part of the last century, their speciality being children's books, which had a fame almost as extensive as those of the great Mr. Newbery himself. He was joined by his brother Thomas, and for two generations a successful business was carried on in this place; the three generations of Dartons were prominent members of the Society of Friends. The house chiefly devoted itself to publishing, but it had a fairly large trade in selling the books issued by other publishers. The firm ceased to exist about the time when the Holborn Valley improvements swept away so many of the old landmarks of that locality. Mr. Joseph W. Darton, the sole partner in Wells Gardner, Darton and Co., is a grandson of the founder of the Holborn Hill house and a great-grandson of the original William Darton. A history of the Dartons would form as interesting a volume as that on John Newbery.

Holborn is an additionally interesting book-locality from the fact that it was from here that some of the first book-catalogues were issued. This important innovation owes much to Charles Davis, whose shop was 'against Gray's Inn.' The earliest of these catalogues which we have seen is a very interesting list of 168 pages octavo, and includes 'valuable libraries, lately purchased, containing near 12,000 volumes in Hebrew, Greek, Latin, French, Italian, Spanish, and English,' 'which will be sold very cheap, the lowest price fix'd in each book, on Thursday, May 7, 1747.' The list is in many respects very curious, not the least of which is that not one of the items offered is priced. One of the facts which strike one most forcibly in this connection is the large capitals which must have been sunk in books even at this early period. Davis, like all the other booksellers—notably Tonson and Lintot—of that period, was a bookseller as well as publisher.

Moving further westward, we find records of bookselling for just a couple of centuries back. Robert Kettlewell was established at the Hand and Sceptre, King's Street, Bloomsbury, whence he issued his kinsman's apparently useful, and certainly very dull, pamphlet, entitled 'Death Made Comfortable; or, The Way to Die Well,' and sold a variety of other books besides. Making a leap of nearly a century, we meet with Samuel Hayes, of Oxford Street, and evidently a relative of John Hayes, to whom we have already referred. Samuel Hayes—when not in a French prison, for he was actually incarcerated by Napoleon when on a visit to France—was at this place of business for sixteen years, 1779 to 1795, and published several catalogues. Isaac Herbert, nephew of the editor of Ames' 'Typographical Antiquities,' was selling books in Great Russell Street in and about 1795; Joseph Bell was established as a bookseller in Oxford Street in the earlier part of the present century; Shepperson and Reynolds were in the same thoroughfare from 1784 to 1793, and sold several very good libraries within the period indicated. Writing in 1790, Pennant mentions that the chapel of Southampton, or Bedford House, Bloomsbury, was at that time rented by Lockyer Davis as a magazine of books. How long it had been in Davis's tenancy is not certain, but he died in 1791. William Davis, the author of several interesting bibliographical books, including two 'Journeys Round the Library of a Bibliomaniac,' was at the Bedford Library, Southampton Row, Holborn, during the early part of the century. Name after name might be quoted if any useful purpose would be served.

There are many links which still connect the Holborn of to-day with the Holborn and immediate district of the past. Three have, however, passed away within recent years. Edward W. Stibbs, whose death occurred in the spring of 1891, at the age of eighty, and whose stock was sold at Sotheby's in the following year, was one of the veterans of the trade, and was essentially of the old school—the school which confined itself almost exclusively to classics. The second removal is that of Mr. J. Brown, whose shop was nearly opposite the entrance to Chancery Lane, and was for nearly thirty years an exceedingly pleasant rendezvous of book-collectors, and whose proprietor was one of the most genial of bibliopoles. The third is Edward Truelove, of 256, High Holborn, the well-known agnostic bookseller, who removed here from the Strand, and who had been in business over forty years. Mr. Truelove retired two or three years since. Further up the road, in New Oxford Street, we find the shop of Mr. James Westell, whose career as a bookseller embraces a period of over half a century, having started in 1841. Mr. Westell first began in a small shop in Bozier's Court, Tottenham Court Road, and this shop has been immortalized by Lord Lytton in 'My Novel,' for it is here that Leonard Fairfield's friendly bookseller was situated. Bozier's Court was a sort of eddy from the constant stream which passes in and out of Oxford Street, and many pleasant hours have been spent in the court by book-lovers. After Mr. Westell left, it passed into the hands of another bookseller, G. Mazzoni, and finally into that of Mr. E. Turnbull, who speaks very highly of it as a bookselling locality. Mr. Turnbull added another shop to the one which was occupied by Mr. Westell; but when the inevitable march of improvements overtook this quaint place three or four years ago, Mr. Turnbull had to leave, and he then took a large shop in New Oxford Street, where he now is. During Mr. Turnbull's tenancy in Bozier's Court several rivals started round about him; but one after another failed to make it pay, and retired, leaving him eventually in entire possession. Another old Holborn bookseller, Mr. George Glashier, who started in 1841, still has a large shop in Southampton Row; not the shop which he occupied for very many years within a few yards of Holborn, but nearer Russell Square, a less crowded thoroughfare than the old place in the same street or row. The shop now occupied by Mr. A. Reader, in Orange Street, Red Lion Square, has been a bookseller's for over half a century, one of the most noted tenants of it being Mr. John Salkeld, who removed nearly twenty years since to Clapham Road, and whose charmingly rustic shop, 'Ivy House,' is quite one of the sights of bookish London.

Indeed, nearly every by-street, as well as the public highway in and around Holborn, has had its bookseller ever since the beginning of the century. Lord Macaulay, C. W. Dilke, W. J. Thoms, Edward Solly, John Forster, and the visions of many other mighty book-hunters, crowd on one's memory in grubbing about after old books in this ancient and attractive, if not always particularly savoury, locality. The two Turnstiles have always been favourites with bibliopoles. Writing in 1881, the late Mr. Thoms said: 'Many years ago I received one of the curious catalogues periodically issued by Crozier, then of Little Turnstile, Holborn. From a pressure of business or some other cause, I did not look through it until it had been in my possession for two or three days, and then I saw in it an edition of "Mist's Letters" in three volumes! In two volumes the book is common enough, but I had never heard of a third volume; neither does Bohn in his edition of Lowndes mention its existence. Of course, on this discovery, I lost no time in making my way to Little Turnstile; and on asking for the "Mist" in three volumes, found, as I had feared, that it was sold. "Who was the lucky purchaser?" I asked anxiously; adding, "Aut Dilke aut Diabolus!" "It was not Diabolus," was Crozier's reply; and I was reconciled when I found the book had fallen into such good hands, and not a little surprised when Crozier went on to say, "But he was not the first to apply for it. Mr. Forster sent for it, but would not keep it, because it was not a sufficiently nice copy."' Both the Great and the Little Turnstiles, Holborn, have always been, as we have said, famous as book-hunting localities, and they still preserve this reputation. In 1636 a publisher and bookseller, George Hutton, was at the 'Sign of the Sun, within the Turning Stile in Holborne.' J. Bagford, the celebrated book-destroyer, was first a shoemaker in the Great Turnstile, a calling in which he was not successful. Then he became a bookseller at the same place, and still success was denied him. At Dulwich College is a library which includes a collection of plays formed by Cartwright, a bookseller of the Turnstile, who subsequently turned actor.

The chief and most enterprising firm of booksellers in Holborn proper is that of Mr. and Mrs. Tregaskis, at No. 232, the corner of the New Turnstile. The house itself is full of interest, and is quite a couple of hundred years old. A century ago one of the most eventful scenes of David Garrick's career was enacted here, for it was from this house that the great actor was buried. Mrs. Tregaskis first started, as Mrs. Bennett, at the corner of Southampton Row, and some time after removing to her present shop, married Mr. James Tregaskis, and the two together have built up a business which is scarcely without a rival in London. The shop is literally crammed with rare and interesting books, whilst 'The Caxton Head Catalogues' are got up with every possible care. Almost next door to the shop for many years occupied by the late Edward Stibbs, Mr. Walter T. Spencer carries on a trade which is almost entirely confined to first editions of modern authors. From Mr. R. J. Parker's shop at 204, the present writer has picked up a very large number of rare and interesting books, including a first edition of Goldsmith—not, however, the 'Vicar'—at exceedingly moderate sums. Mr. E. Menken, of Bury Street, New Oxford Street, is one of the most successful booksellers of recent years, and his stock is both large and select. Mr. Menken first started in Gray's Inn Road, nearly opposite the Town Hall, five or six years ago, subsequently removing to Bury Street; but his business grew so rapidly that he had to take the adjoining shop into his service. Mr. Menken's model catalogues invariably contain something which every book collector feels it is absolutely necessary to have. He is a man of versatile abilities, literary and otherwise, and includes among his customers no less a person than Mr. Gladstone. Messrs. Bull and Auvache, of 35, Hart Street, Bloomsbury, are extensive dealers in editions of the classics and Bibles. At one time there were no less than four second-hand booksellers in Hyde Street, New Oxford Street, but at present there is only one. Next door but one to Mudie's, we have the shop of Mr. James Roche, who is a link with the past, having started in 1850, and for many years carried on business in a little corner shop in Southampton Row, one door from the Holborn highway. Messrs. J. Rimell and Sons, noted for their extensive collection of works on the fine arts and architecture, are at 91, Oxford Street. Among the literary booksellers of the first quarter of the present century, William Goodhugh, of 155, Oxford Street, deserves a mention here. 'The English Gentleman's Library Manual,' 1827, is his best-known work, although from a literary standpoint it is a poor concern; he also wrote 'Gates' to the French, Italian, Spanish, Hebrew, Arabic and Syriac, 'unlocked by new and easy methods.' Goodhugh was conversant with several of the Oriental and many European languages. His knowledge of books was a very extensive and profound one, and as a literary bookseller he is an interesting figure in the annals of bibliopolic history. Fifty years ago many good books were picked up out of 'Miller's Catalogue of Cheap Books,' which appeared monthly from 404, Oxford Street, that for September, 1845, being numbered 127. A quarter of a century ago there were several booksellers in Oxford Street, e.g., G. A. Davies, at 417; W. Heath, at 497; J. Kimpton, at 303; E. Lumley, at 514; J. Pettit, at 528; and Whittingham.

The further west one goes, the less interesting do the annals of bookselling become, for Oxford Street is essentially a modern locality, and second-hand bookselling never has thrived much in new localities. It was, however, when rummaging over the contents of a stall in a Wardour Street alley that Charles Lamb lighted upon a ragged duodecimo, which had been the delight of his infancy. The price demanded was sixpence, which the owner, himself a squab little duodecimo of a character, enforced with the asseverance that his own mother should not have it for a farthing less, supplementing the assertion with an oath and 'Now, I have put my soul to it.' The book was the 'Queen Like Closet,' which, it is scarcely necessary to say, Elia rescued from the man of profanity. Soho has long been more or less of a bookselling quarter. John Paul Manson, who was in King Street, Westminster, in 1786, and issued from thence 'A Summer Catalogue' in 1795, subsequently removed to Gerard Street, Soho, and died in 1812. He was especially well versed, not only in Caxtons, but in all the best works of the early printers, and many English black-letter books passed through his hands. Dibdin observes that Professor Heyne could not have exhibited greater signs of joy at the sight of the Towneley manuscript of Homer than did Manson on the discovery of Rastell's 'Pastyme of the People' among the books of Mr. Brand. Two sons of this Manson subsequently became partners in the firm of Christie, the art auctioneers. The first Sampson Low started as a bookseller in Berwick Street, Soho, in or about 1790.

Day's Library, the second oldest existing circulating library in London (the oldest is that of Cawthorn and Hutt, established in 1744, Cockspur Street), has continued from the year 1776 within a few hundred yards of its present situation. In that year a Mr. Dangerfield established it on the north side of Berkeley Square, and it was purchased from him by Mr. Rice in 1810 or 1811, under whom it largely developed in extent and reputation. In 1818 he removed into the adjoining Mount Street at No. 123 (south side), where for about fifty years the library remained. Meanwhile it became the property of Mr. Hoby, and after one or two changes successively of Mr. John and Mr. Charles Day, father and son. In Mr. John Day's hands it crossed the road to No. 16 on the north side, and remained there about twenty-four years, till that part of Mount Street was cleared to make way for the present Carlos Place. Then in the year 1890 it again crossed the road to No. 96, where Mr. Charles Day holds a long lease. An early catalogue of the institution shows that the eighteenth-century circulating libraries contained a portion of the weightier works, such as history, biography, travels, etc., a fact which is rarely realized in the face of the popular impression that it was left to the late Mr. C. E. Mudie to supply such works.

Copyright © D. J.McAdam· All Rights Reserved